Bar Kokhba revolt

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136;[1] Hebrew: מרד בר כוכבא or mered bar kokhba) against the Roman Empire was the third major rebellion by the Jews of Iudaea Province (also spelled Judaea) and the last of the Jewish-Roman Wars. Simon bar Kokhba, the commander of the revolt, was acclaimed as a Messiah, a heroic figure who could restore Israel. The revolt established an independent state of Israel over parts of Judea for over two years, but a Roman army of 12 legions with auxiliaries finally crushed it. The Romans then barred Jews from Jerusalem, except to attend Tisha B'Av. Although Jewish Christians hailed Jesus as the Messiah and did not support Bar Kokhba, they were barred from Jerusalem along with the rest of the Jews. The war and its aftermath helped differentiate Christianity as a religion distinct from Judaism, see also List of events in early Christianity. The revolt is also known as The Second Jewish-Roman War, The Second Jewish Revolt, The Third Jewish-Roman War or The Third Jewish Revolt (counting the Kitos War, 115 - 117, as second).

Contents |

Background

After the failed Great Jewish Revolt in 70 CE, the Roman authorities took measures to suppress the rebellious province. Instead of a procurator, they installed a praetor as a governor and stationed an entire legion, the X Fretensis. Because the Revolt had resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem, the Sanhedrin at Yavne provided spiritual guidance for the Jewish nation, both in Judea and throughout the Jewish diaspora.

In 130, Emperor Hadrian visited the ruins of Jerusalem. At first sympathetic towards the Jews, Hadrian promised to rebuild the city, but the Jews felt betrayed when they found out that his intentions were to rebuild the Jewish holiest city as a Roman metropolis, and a new temple upon the ruins of the Second Temple, which was to be dedicated to Jupiter.[2]

An additional legion, the VI Ferrata, was stationed in the province to maintain order, and the works commenced in 131 after the governor of Judaea Tineius Rufus performed the foundation ceremony of Aelia Capitolina, the city’s projected new name. "Ploughing up the Temple" was a religious offence that turned many Jews against the Roman authorities. The tensions grew higher when Hadrian abolished circumcision (brit milah), which he, a Hellenist, viewed as mutilation.[3] A Roman coin inscribed Aelia Capitolina was issued in 132.

Revolt

The Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva (alternatively Akiba) indulged the possibility that Simon Bar Kokhba could be the Jewish Messiah, based on the meaning of his name ("Bar Kokhba" means "son of a star" in the Aramaic language) and the Star Prophecy verse from Numbers 24:17: "There shall come a star out of Jacob"[4]

At the time, Jewish Christians were still a minor sect of Judaism, and most historians believe that it was this messianic claim in favor of Bar Kokhba alienated many of them, who believed that the true Messiah was Jesus, and sharply deepened the schism between Jews and Christians.

The Jewish leaders carefully planned the second revolt to avoid numerous mistakes that had plagued the first Great Jewish Revolt sixty years earlier. In 132, a revolt led by Bar Kokhba quickly spread from Modi'in across the country, cutting off the Roman garrison in Jerusalem.

Roman reaction

The outbreak took the Romans by surprise. Hadrian called his general Sextus Julius Severus from Britain, and troops were brought from as far as the Danube. The size of the Roman army amassed against the rebels was much larger than that commanded by Titus sixty years earlier. Roman losses were very heavy. The XXII Deiotariana was disbanded after serious losses.[5][6]

The struggle lasted for three years before the revolt was brutally crushed in the summer of 135. After losing Jerusalem, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of Betar, which also subsequently came under siege. The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the numbers slain were enormous, that the Romans "went on killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils".[7] The Talmud also relates that for seventeen years the Romans did not allow the Jews to bury their dead in Betar.

"The Era of the redemption of Israel"

A sovereign Jewish state was restored for two and a half years that followed. The functional public administration was headed by Simon Bar Kokhba, who took the title Nasi Israel (ruler or prince of Israel). The "Era of the redemption of Israel" was announced, contracts were signed and coins were minted in large quantity in silver and copper with corresponding inscriptions (all were struck over foreign coins).

Rabbi Akiva presided over the Sanhedrin. The religious rituals were observed and the korbanot (i.e., sacrifices) were resumed on the Altar. It has been believed that attempts were made to restore the Temple in Jerusalem, but the evidence—letters written in Jerusalem and dated to the revolutionary era—has turned out to belong to the revolt of 66–70.

Outcome of the war

According to Cassius Dio, 580,000 Jews were killed, and 50 fortified towns and 985 villages razed.[8][9] The Talmud, however, claims a death toll in the millions. The latter figure is unlikely, because there were simply not that many Jews in the region at that time. Cassius Dio claimed that "Many Romans, moreover, perished in this war. Therefore, Hadrian, in writing to the Senate, did not employ the opening phrase commonly affected by the emperors: 'If you and your children are in health, it is well; I and the army are in health.'"[2]

Hadrian attempted to root out Judaism, which he saw as the cause of continuous rebellions. He prohibited the Torah law and the Hebrew calendar, and executed Judaic scholars. The sacred scroll was ceremonially burned on the Temple Mount. At the former Temple sanctuary, he installed two statues, one of Jupiter, another of himself. In an attempt to erase any memory of Judea or Ancient Israel, he wiped the name off the map and replaced it with Syria Palaestina, after the Philistines, the ancient enemies of the Jews; previously, similar terms had been used to describe only the (smaller) former Philistine homeland to the west of Judaea. Since then, the land has been referred to as "Palestine," which supplanted earlier terms such as "Iudaea" (Judaea) and Israel. Similarly, he re-established Jerusalem as the Roman pagan polis of Aelia Capitolina, and Jews were forbidden from entering it. Unfortunately for Hadrian, Rabbinic Judaism had already become a portable religion, centered around synagogues, and the Jews themselves kept books and dispersed throughout the Roman world and beyond.

According to a Rabbinic midrash, in addition to Bar Kochba the Romans executed ten leading members of the Sanhedrin: the high priest, R. Ishmael; the president of the Sanhedrin, R. Shimon ben Gamaliel; R. Akiba; R. Hanania ben Teradion; the interpreter of the Sanhedrin, R. Huspith; R. Eliezer ben Shamua; R. Hanina ben Hakinai; the secretary of the Sanhedrin, R. Yeshevav; R. Yehuda ben Dama; and R. Yehuda ben Baba. The Rabbinic account describes agonizing tortures: R. Akiba was flayed, R. Ishmael had the skin of his head pulled off slowly, and R. Hanania was burned at a stake, with wet wool held by a Torah scroll wrapped around his body to prolong his death.

Long-term consequences and historic importance

Constantine I allowed Jews to mourn their defeat and humiliation once a year on Tisha B'Av at the Western Wall. Jews remained scattered for close to two millennia; their numbers in the region fluctuated with time.

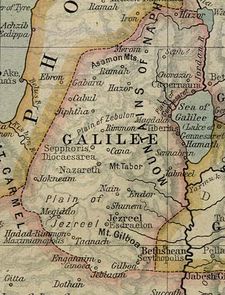

Modern historians have come to view the Bar-Kokhba Revolt as being of decisive historic importance. The massive destruction and loss of life occasioned by the revolt has led some scholars to date the beginning of the Jewish diaspora from this date. They note that, unlike the aftermath of the First Jewish-Roman War chronicled by Josephus, the majority of the Jewish population of Judea was either killed, exiled, or sold into slavery after the Bar-Kokhba Revolt, and Jewish religious and political authority was suppressed far more brutally. After the revolt the Jewish religious center shifted to the Babylonian Jewish community and its scholars. Judea would not be a center of Jewish religious, cultural, or political life again until the modern era, though Jews continued to live there and important religious developments still occurred there. In Galilee, the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled in the 2nd–4th centuries. Eventually, Safed became known as a center of Jewish learning, especially Kabbalah in the 15th century.

Historian Shmuel Katz writes that even after the disaster of the revolt:

"Jewish life remained active and productive. Banished from Jerusalem, it now centred on Galilee. Refugees returned; Jews who had been sold into slavery were redeemed. In the centuries after Bar Kochba and Hadrian, some of the most significant creations of the Jewish spirit were produced in Palestine. It was there that the Mishnah was completed and the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled, and the bulk of the community farmed the land."[10]

Katz lists the communities left in Palestine:

"43 Jewish communities in Palestine in the sixth century: 12 on the coast, in the Negev, and east of the Jordan, and 31 villages in Galilee and in the Jordan valley."[10]

The disastrous end of the revolt also occasioned major changes in Jewish religious thought. Messianism was abstracted and spiritualized, and rabbinical political thought became deeply cautious and conservative. The Talmud, for instance, refers to Bar-Kokhba as "Ben-Kusiba", a derogatory term used to indicate that he was a false Messiah. The deeply ambivalent rabbinical position regarding Messianism, as expressed most famously in the Rambam's (also known as Maimonides) "Epistle to Yemen", would seem to have its origins in the attempt to deal with the trauma of a failed Messianic uprising.

In the post-rabbinical era, however, the Bar-Kokhba Revolt became a symbol of valiant national resistance. The Zionist youth movement Betar took its name from Bar-Kokhba's traditional last stronghold, and David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister, took his Hebrew last name from one of Bar-Kokhba's generals.

A popular children's song, included in the curriculum of Israeli kindergartens, has the refrain "Bar Kokhba was a Hero/He fought for Liberty" and its words describe Bar Kokhba as being captured, thrown into a lion's den but managing to escape riding on the lion's back.

Yehoshafat Harkabi, a prominent columnist and former chief of Israeli military intelligence, marked his transition from hardliner to supporter of creating a Palestinian state with a 1978 open letter to then Prime Minister Menachem Begin, in which he termed Bar Kokhva "an irresponsible adventurer who brought disaster upon the Jewish People" -- drawing an explicit contemporary parallel to Israel's holding on to the Occupied Territories, which in Harkabi's view might cause a new such disaster.[11]

Further revolts against the Roman Empire

In 351-352, the Jews launched yet another revolt, provoking once again heavy retribution.[10]

In 438, when the Empress Eudocia removed the ban on Jews' praying at the Temple site, the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call "to the great and mighty people of the Jews" which began: "Know that the end of the exile of our people has come"![10][12]

In the belief of restoration to come, the Jews made an alliance with the Persians who invaded Palestine in 614, fought at their side, overwhelmed the Byzantine garrison in Jerusalem, and for five years governed the city.[10]

Sources

The best recognized sources are Cassius Dio, Roman History (book 69) and Aelius Spartianus, Life of Hadrian (in the Augustan History). The discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls has added some new historical data.

See also

- Bar Kochba Revolt coinage

References

- ↑ for the year 136, see: W. Eck, ' The Bar Kokhba Revolt: The Roman Point of View', pp. 87-88.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cassius Dio, Roman History

- ↑ Christopher Mackay. "Ancient Rome a Military and Political History" 2007: 230

- ↑ Book of Numbers 24:17: There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all the children of Sheth.

- ↑ L. J. F. Keppie (2000) Legions and veterans: Roman army papers 1971-2000 Franz Steiner Verlag, ISBN 3515077448 pp 228-229

- ↑ livius.org account(Legio XXII Deiotariana)

- ↑ Ta'anit 4:5

- ↑ The 'Five Good Emperors' (roman-empire.net)

- ↑ Mosaic or mosaic?—The Genesis of the Israeli Language by Zuckermann, Gilad

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Katz, Shmuel, Battleground, (1974), page 96

- ↑ Published by the Peace Now movement, of which Harkabi was a founding member [1].

- ↑ Avraham Yaari, Igrot Eretz Yisrael (Tel Aviv, 1943), p. 46.

Further reading

- Yohannan Aharoni & Michael Avi-Yonah, "The MacMillan Bible Atlas", Revised Edition, pp. 164–65 (1968 & 1977 by Carta Ltd.)

- The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters (Judean Desert studies). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963–2002.

- Vol. 2, "Greek Papyri", edited by Naphtali Lewis; "Aramaic and Nabatean Signatures and Subscriptions", edited by Yigael Yadin and Jonas C. Greenfield. (ISBN 9652210099).

- Vol. 3, "Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean–Aramaic Papyri", edited Yigael Yadin, Jonas C. Greenfield, Ada Yardeni, Baruch A. Levine (ISBN 9652210463).

- W. Eck, 'The Bar Kokhba Revolt: the Roman point of view' in the Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999) 76ff.

- Faulkner, Neil. Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7524-2573-0).

- Goodman, Martin. The Ruling Class of Judaea: The Origins of the Jewish Revolt against Rome, A.D. 66–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-33401-2); 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0-521-44782-8).

- Richard Marks: The Image of Bar Kokhba in Traditional Jewish Literature: False Messiah and National Hero: University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 1994: ISBN 0-271-00939-X

- David Ussishkin: "Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold", in: Tel Aviv. Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 20 (1993) 66ff.

- Yadin, Yigael. Bar-Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. New York: Random House, 1971 (hardcover, ISBN 0394471849); London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971 (hardcover, ISBN 0297003453).

- Mildenberg, Leo. The Coinage of the Bar Kokhba War. Switzerland: Schweizerische Numismatische Gesellschaft, Zurich, 1984 (hardcover, ISBN 3-7941-2634-3).

External links

- photographs from Yadin's book Bar Kokhba

- The Jewish History Resource Center Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- David Pileggi, "The Bar Kochva letters": discovery of the papyri

- Archaeologists find tunnels from Jewish revolt against Romans by the AP. Ha'aretz March 14, 2006

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Bar Kokba and Bar Kokba War

- Bar Kochba with links to all sources

- "Should we continue to educate young Israelis to emulate Bar Kokhba?" - 1983 article (in Hebrew)

|

||||||||||||||||||||